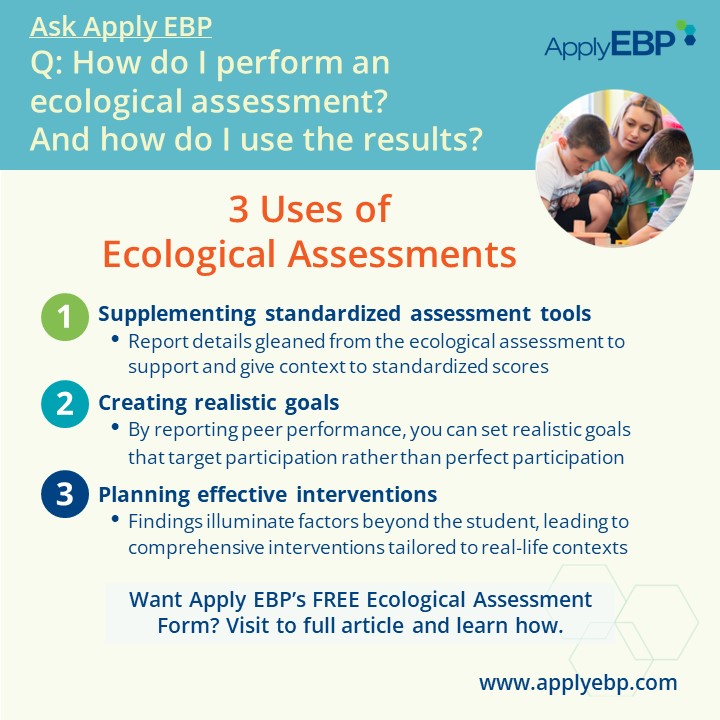

Ask Apply EBP

3 Uses of Ecological Assessments, Plus a Free Ecological Assessment Form

Q: How do I perform an ecological assessment? And how do I use the results?

In our article “Must-Have Test and Organizing Your School-based Assessment”, we emphasize the importance of initiating assessments by evaluating your pediatric client’s level of participation. One way to do this is via an Ecological Assessment. While an ecological assessment is not a standardized test, the use of a form can bring some formality to the observation. When used repeatedly for the same activity, it can make it easier to compare previous and current performance. Additionally, you will find in the bottom of this article a way to get Apply EBP’s free Ecological Assessment Form.

What Are Ecological Assessments For?

Here are 3 great uses of an ecological assessment:

1. Supplementing Standardized Assessments Tools

Haney and Cavallaro (1996) states that an ecological assessment can be “an alternative and/or supplement to norm-referenced and criterion-referenced testing.” While a standardized test can provide you with numbers, it may not give you enough details about the student’s actual performance. This is where an ecological assessment excels!

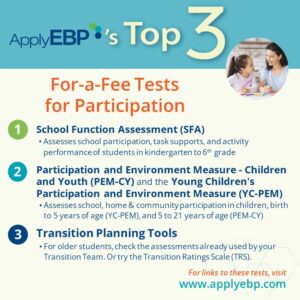

For example, when using the School Function Assessment (SFA), you may report under Part I that Johnny’s Participation is a 4 out of 6 for Classroom (i.e., he requires intermittent assistance). The ecological assessment will give you the details to report how he performed, the strengths he displayed, and the types of assistance he needed.

Additionally, an ecological assessment can help you understand the impact of other test results in the child’s real life. For example, you might find that the child’s difficulty with the Timed Floor to Stand test is realized during transition time standing to sitting on the mat during Circle Time.

On the other hand, you may also find the lack of impact of test results in the child’s real life. For example, you might find that despite differences found in the Sensory Processing Measure 2 that a student is able to participate in a loud PE class, especially when the child is participating in their preferred activity.

Indeed, this underscores the importance emphasized in our article, “Must-Have Test and Organizing Your School-based Assessment”, where we advocate for commencing assessments at the participation level. Doing so helps sidestep the intricate explanations required for a low score on a body function and structure level test, like the SPM-2, especially when the child’s participation aligns with expectations. However, should you find yourself in such a predicament, ecological assessment results can help with informed decision-making. For instance, in the aforementioned scenario, you might recommend integrating Johnny’s preferred interests into activities to optimize his engagement.

2. Creating Realistic Goals

Frequently, students with disabilities are given IEP goals that surpass the expectations set for their peers. For instance, goals like navigating the hallway without bumping into others or producing two paragraphs with at least 90% legibility for five consecutive days. Observing how peers navigate similar tasks offers a tangible benchmark for understanding classroom dynamics and typical peer behavior.

As we always say in Apply EBP, when creating goals, seek participation, and NOT “perfect participation.” Students with disabilities should be allowed to make errors, have bad days, and simply be kids – twirling, and chatting with their peers during arrival – just like their peers.

So, use the information gleaned from the ecological assessment about Expected Participation as a starting point. Then integrate observations of Peer Performance to inform the goal-setting process for your students, ensuring that objectives are both realistic and conducive to their overall development and inclusion within the classroom community.

3. Planning Effective Interventions

Assessing a student solely in isolation often leads to interventions that narrowly focus on addressing the student’s individual impairments. However, employing an ecological assessment broadens the scope, allowing for the identification of potential sources of difficulty beyond the student, such as environmental factors, instructional methods, and task materials.

Through this ecological lens, you’re prompted to devise interventions aimed at enhancing the student’s performance within real-life contexts. This approach prompts critical questions: What adaptations and accommodations are necessary to enable the student to complete tasks independently? How can the environment be modified to facilitate participation? Are there adjustments that can be made to instructions to better suit the student’s needs?

Consider this scenario: The teacher reports that Johnny struggles to complete journal writing activities, despite his ability to write in a separate setting. Conducting an ecological assessment during a journal writing session reveals that Johnny faces challenges initiating writing on the topic of “My Favorite Animal,” possibly indicating difficulty focusing or coming up with ideas, and not a problem in the physical act of handwriting! In response, you might suggest engaging the class in pre-writing discussions or refining the topic to align with Johnny’s interests, such as favorite pets or zoo animals. Alternatively, providing a word list relevant to the topic could support Johnny and his peers in generating ideas.

Similarly, in physical education, an ecological assessment reveals that Jamie refrains from participating in throw-and-catch games due to her difficulty handling the materials. As an intervention, you can collaborate with the PE teacher to offer a variety of materials would allow Jamie to participate and develop throwing and catching skills.

Start Your Ecological Assessment Journey Now

Of course, there are many more uses of Ecological Assessments. As you engage in more ecological assessments, you’ll uncover additional applications and insights. For instance, when conducted repeatedly, you can use an ecological assessment to report on progress. You might also opt to conduct spontaneous, on-the-fly mini-ecological assessments as a component of your embedded interventions (Anaby et al, 2019) to swiftly address emerging classroom challenges (for more on this, read the article 5 Skilled Services We Can Provide When Embedding in the Student’s Real-life Environment).

Want a free ecological assessment form?

Join Apply EBP’s Facebook Discussion Group by clicking here where you can download one from the group “Files” section.

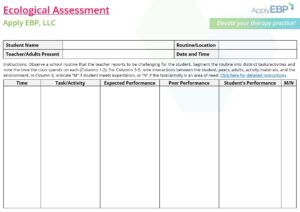

This form is free to use. Should it be copied or adapted, please include a citation back to the source as: “Apply EBP, LLC | www.applyebp.com”.

How to Use the Form

Let’s break down how to get the most out of this form:

-

-

- INTERVIEW: Start by gathering information from the teacher to identify the specific classroom or school routine that presents challenges for the student.

- GENERAL INFORMATION: Fill out the top part of the form, including details like the routine, location, adults present, and the observation date and time frame.

- OBSERVE: Observe the student in the classroom without interacting with them or the classroom environment.

- TIME & TASK/ACTIVITY: Segment the routine into distinct tasks or activities and note the time spent on each. For example, the arrival routine may include the distinct actions of:

- 8:20-8:25 am: Put away bag/jacket, and walk to sit on mat

- 8:30-8:50 am: Early morning discussions (weather, day’s agenda, etc.)

- 8:50-9:00 am: Stand up, retrieve ELA materials, and walk to sit on chair

- EXPECTED PERFORMANCE: Describe the teacher’s expectations or what successful completion of each task or activity looks like.

- For example, for the 1st task above, the students are expected to doff and hang jacket on hook, place bag in cubby, then quietly head to the mat and sit on their spot

- PEER PERFORMANCE: Observe and report on what other students are doing during the same activities to provide context.

- For example, for the 1st task above you may report that: Many students chat while putting away bags and jackets. 4 students required multiple attempts to get jackets on the hook. 2 required physical assistance from the teacher. Some walk “silly” to the mat. Students use different strategies for transitioning from standing to sitting down on the mat.

- STUDENT PERFORMANCE: Next is the time to describe what the student you are assessing is actually doing. Since participation does not occur in isolation, make sure to report on the interactions between the student, the task, and the physical and social environment:

- How is the student completing the task?

- What are the student’s strengths as it relates to task completion?

- Is the student able to follow the task steps or instructions?

- Does the student require assistance or accommodations to complete it?

- How is the physical environment impacting performance?

- How is the social environment (peers, adults, class culture, etc.) impacting performance?

- MEETS EXPECTATIONS?: Finally, mark M if the student is able to meet expected performance, or N if the activity is an area of need or challenge for the student. You may also mark the activity as both “M/N”, if the student meets expectations, but it remains an area of need that you think can be improved further (e.g., it took the student much longer to complete the task, or the student requires too much assistance).

While non-participation-based goals are not inherently bad, they might be most effective when targeting clinical outcomes, like increasing ankle range of motion when serial casting or enhancing dexterity post-surgery.

-

Head on to Apply EBP’s Facebook Group page to download and start using our Free Ecological Assessment Form now to continue your journey towards better and best practice, and success for your pediatric clients in school!

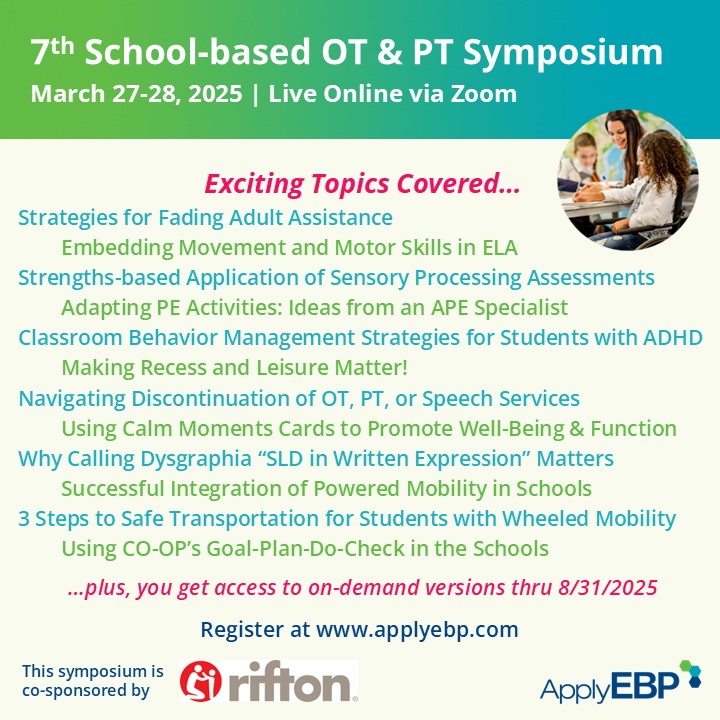

If you would like to learn more about best practices in the school setting, join…

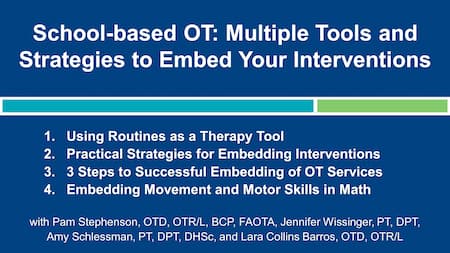

Or these webinars…

References:

Anaby, D. R., Campbell, W. N., Missiuna, C., Shaw, S. R., Bennett, S., Khan, S., … & GOLDs (Group for Optimizing Leadership and Delivering Services). (2019). Recommended practices to organize and deliver school‐based services for children with disabilities: A scoping review. Child: care, health and development, 45(1), 15-27.

Haney, M., & Cavallaro, C. C. (1996). Using ecological assessment in daily program planning for children with disabilities in typical preschool settings. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 16(1), 66-81.

Find More Answers to Your Questions in Our...

Featured School

Symposium

Featured Live

Workshop

Featured On-Demand

Webinar

Routines as a Therapy Tool

Featured Webinar

Bundle

School-based OT: Embedded Interventions Bundle

Have a question?

Submit here…

*Clicking submit will send your question directly to our email inbox. Your name and email will let us know that your submission is real (not spam). We will not include these in our posts, unless you tell us to include your name. Please read our privacy policy here.

All infographics and videos on www.applyebp.com are intellectual properties of Apply EBP, LLC

You may use the infographics and videos for free for any non-commercial, educational purposes. Please cite the source as “Apply EBP, LLC” and a link to the source article. If you plan to use any infographic or video for commercial purposes (i.e., for profit), please email Carlo@applyebp.com to obtain a written permission. Permission can be granted on a case-by-case basis.