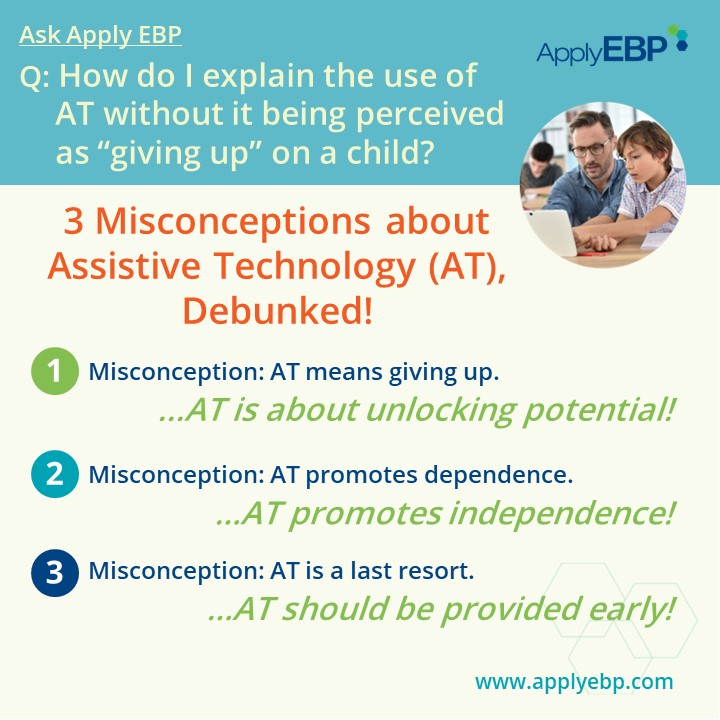

Ask Apply EBP

3 Misconceptions about Assistive Technology (AT), Debunked!

Q: How do I explain the use of assistive technology without it being perceived as “giving up” on a child?

A: We all know that Assistive Technology (AT) plays a pivotal role in enhancing the lives of children with disabilities. However, misconceptions and resistance often hinder its adoption and implementation. In this article, we aim to debunk three prevalent misconceptions surrounding AT. We hope that this discussion will help you share with your team the transformative potential of AT and advocate for its early adoption.

But before we continue, here are technical definitions from IDEA:

-

-

- “assistive technology device” means any item, piece of equipment, or product system, whether acquired commercially off the shelf, modified, or customized, that is used to increase, maintain, or improve functional capabilities of a child with a disability.

- “assistive technology service” means any service that directly assists a child with a disability in the selection, acquisition, or use of an assistive technology device

-

To facilitate our discussions in this article, we will use the term Assistive Technology (AT) interchangeably with AT, in general, and with an AT device. AT includes, but are not limited to mobility devices, activities of daily living tools, computer technology, and more.

Misconception #1: AT means giving up.

AT is often misunderstood as an admission of defeat or giving up on a child’s abilities. Contrary to this notion, AT signifies a belief in the child’s untapped potential for learning and development. However, their potential can be obscured by impairments or brain and body differences associated with their diagnoses. And we now know that such impairments or differences are often lifelong and not as amenable to change.

The role of AT is to unlock their potential by bypassing such impairments, as well as by taking advantage of the strength their differences bring, so that the child can focus on honing skills that are meaningful to their schooling (Young & McCormack, 2018; McNichol et al, 2021). For example:

-

-

- Keyboarding with spell-check that bypasses spelling difficulties in dyslexia, to aid a student in written expression

- Gait trainer that bypass physical impairments in children with cerebral palsy to facilitate navigation and exploration of their school environment

- Communication devices that bypass speaking difficulties for non-speaking autistic students to promote their ability to advocate for their needs

-

Another reason that AT is seen as giving up is the parents’ and educators’ fear that it means the end of support from related services. However, this is not the case. Service providers can still play a vital and at times bigger role, focusing on more meaningful goals. AT shifts therapy and school goals from splinter skills to real-life skills that enable children to succeed in education and daily living. For example, goals shift from letter formation to written expression, from physical strength to active recess participation, and from sounding out words to effective communication during mealtime.

Lesson #1: AT does not mean giving up. AT is about unlocking potential.

Misconception #2: AT promotes dependence.

The use of AT is wrongly perceived by some as fostering dependence and inhibiting skill development. However, this stems from a societal stigma rooted in the Medical Model of Disability (WHO & UNICEF, 2022). The Medical Model primarily associates the challenge of participation with an individual’s impairments, and considers such impairments as needing “fixing” (Chen & Patten, 2021).

In its place, we need to embrace the Social Model of Disability, to recognize differences as natural variations, and disabilities as resulting from social contexts that fail to support individual differences (Chen & Patten, 2021). From this perspective, AT serves as a tool for independent participation – often, instant independent participation – akin to the impact of prescription glasses in one’s ability to navigate and interact with their environment.

This is borne by multiple research that shows AT promotes independence in participation in education, recreation, and social activities; accessing higher education and jobs; and carrying out household activities (WHO & UNICEF, 2022). AT also results in the following psychological benefits: autonomy, motivation, self-expression, and sense of belonging (Fernández-Batanero et al, 2022). So, rather than fearing dependence in AT, we should strive to empower children’s independence by making their AT accepted and supported by their physical and social environment.

Lesson #2: AT does not promote dependence. It promotes independence!

Misconception #3: AT is a last resort.

AT devices are often introduced late due to the misconception that they should be reserved as a last resort. However, delaying the provision of AT impedes a child’s ability to maximize their potential and develop independence (as discussed in numbers 1 and 2 above).

Livingstone & Field (2015) reported that an AT user see the device as a part of oneself; it is not a prop! Thus, early AT introduction is paramount to allow children to incorporate the AT device into their daily routines and cultivate mastery over its use. As Botelho (2021) stated “It is well understood that the earlier in a child’s life that an experience takes place, the greater the long-term consequences…stakeholders can maximize the positive impact of their actions by prioritizing the early childhood period.”

Embracing AT early as a norm sets the stage for future achievements. It also fosters a supportive social environment that is conducive to growth and independence. Where there is continued resistance in early use of AT, you can discuss the use of AT “in parallel.” For example, writing for shorter tasks and keyboarding for essays; or using a wheelchair to get to the playground where they can play with peers using their walker.

Lesson #3: AT should not be a last resort. It should be provided early to maximize its impact.

Conclusion:

By dispelling these misconceptions and advocating for early introduction of AT, we can pave the way for a more inclusive and empowering approach to learning and development. AT, when embraced proactively and integrated thoughtfully, has the potential to unlock the full potential of children with disabilities. Let us champion the crucial role of AT in fostering independent participation across all facets of life!

If you are interested in more evidence-based discussions surrounding AT, join…

References:

Botelho, F. H. (2021). Childhood and Assistive Technology: Growing with opportunity, developing with technology. Assistive Technology, 33(sup1), 87-93.

Chen, Y. L., & Patten, K. (2021). Shifting Focus From Impairment to Inclusion: Expanding Occupational Therapy for Neurodivergent Students to Address School Environments. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 75(3), 7503347010p1-7503347010p7

Fernández-Batanero, J. M., Montenegro-Rueda, M., Fernández-Cerero, J., & García-Martínez, I. (2022). Assistive technology for the inclusion of students with disabilities: a systematic review. Educational technology research and development, 70(5), 1911-1930.

Global report on assistive technology. Geneva: World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), 2022. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

Hammel, J., Magasi, S., Heinemann, A., Gray, D. B., Stark, S., Kisala, P., … & Hahn, E. A. (2015). Environmental barriers and supports to everyday participation: A qualitative insider perspective from people with disabilities. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 96(4), 578-588.

Livingstone, R., & Field, D. (2015). The child and family experience of power mobility: a qualitative synthesis. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 57(4), 317-327.

McNicholl, A., Casey, H., Desmond, D., & Gallagher, P. (2021). The impact of assistive technology use for students with disabilities in higher education: a systematic review. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 16(2), 130-143.

Young, G., & MacCormack, J. (2018, May 4). Assistive technology for students with learning disabilities. LD@school. https://www.ldatschool.ca/assistive-technology/

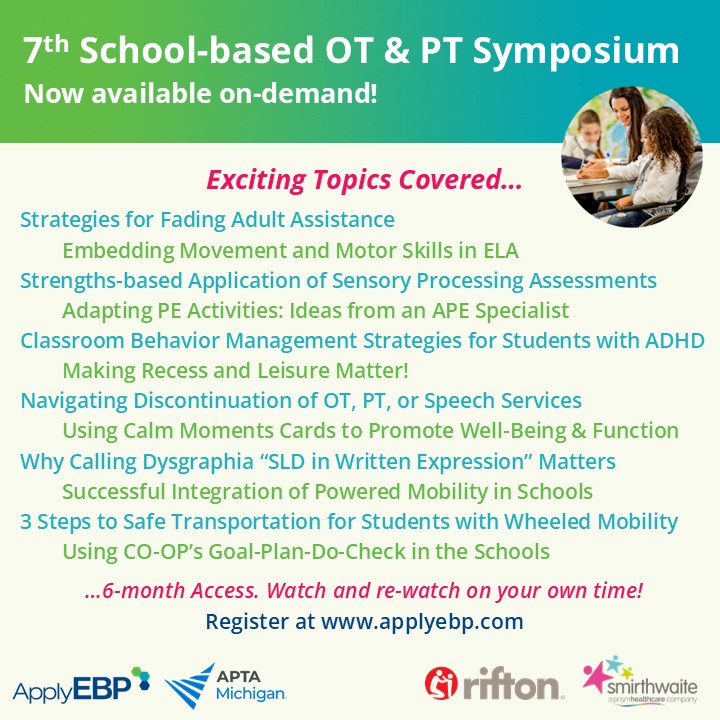

Find More Answers to Your Questions in Our...

Featured School

Symposium

7th Online School-based OT and PT Symposium - On-Demand Version

- Watch and re-watch on your own time

- On-Demand Version

- OTs, OTAs, PTs and PTAs

- $399-449

Featured Live

Workshop

6th Online School-based OT and PT Symposium - On-demand Version

- Watch and re-watch on your own time

- On-Demand Version

- OTs, OTAs, PTs and PTAs

- $399-449

Featured On-Demand

Webinar

Promoting Daytime Function with a 24-Hour Postural Care Plan

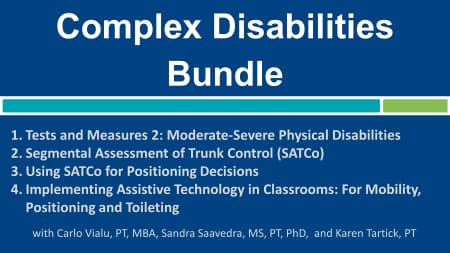

Featured Webinar

Bundle

Complex Disabilities Bundle

Have a question?

Submit here…

*Clicking submit will send your question directly to our email inbox. Your name and email will let us know that your submission is real (not spam). We will not include these in our posts, unless you tell us to include your name. Please read our privacy policy here.

All infographics and videos on www.applyebp.com are intellectual properties of Apply EBP, LLC

You may use the infographics and videos for free for any non-commercial, educational purposes. Please cite the source as “Apply EBP, LLC” and a link to the source article. If you plan to use any infographic or video for commercial purposes (i.e., for profit), please email Carlo@applyebp.com to obtain a written permission. Permission can be granted on a case-by-case basis.