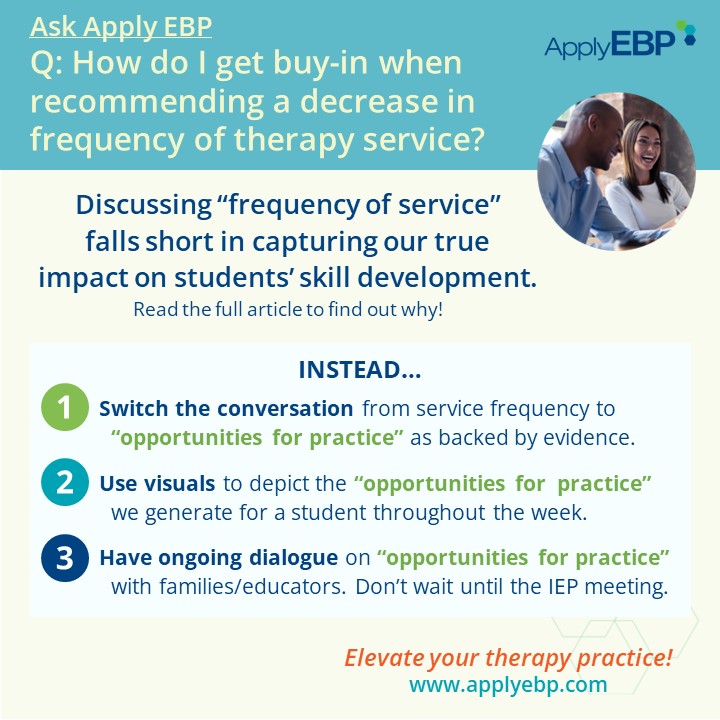

Ask Apply EBP

Shifting Conversations from “Frequency of Services” to “Opportunities for Practice”

Q: I am recommending a decrease in frequency of services for a student at an upcoming IEP meeting. How do I convince the team to buy in to my recommendations?

When discussing the frequency of our services, it’s essential to shift the focus from mere numbers to the quality of practice opportunities we provide. Rather than fixating on how often a child receives therapy, we should emphasize the depth and breadth of learning experiences we cultivate.

Consider this: if all families hear is the amount of time we work directly with their children, say 1x a week for 30 minutes, they may mistakenly assume that learning only occurs during those brief sessions. Consequently, when it comes time to adjust service frequency, concerns about decreased practice time may arise: “He used to practice once a week, now he will only practice once a month? That does not sound like enough time!”

To combat this misconception, we, at Apply EBP, propose a shift in terminology. Let’s replace discussions of “frequency of services” with a focus on the “opportunities for practice” we facilitate to happen. Learning, after all, thrives on consistent and varied practice.

How Much Practice Is Needed to Achieve a Goal?

To grasp the significance of “opportunities for practice,” let’s delve into some illuminating research findings:

-

-

- Walking Mileage: Toddlers, in their quest to master walking, cover an astonishing distance daily, the length of ~46 football fields (Adolph et al, 2012). Now, think about the children we are working with. Are we able to give this much practice in 30 minutes, once a week?

- Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD): The American Physical Therapy Association’s Clinical Practice Guideline for DCD estimates that it takes about 2-5x a week of practice for ~9 weeks to gain a skill (Dannemiller et al, 2020). How feasible is providing services 3, 4, or 5x a week for a child with DCD?

- Upper Limb Training in Cerebral Palsy (CP): Jackman et al (2020) found that it takes ~25 hours of functional upper limb training for children with CP to achieve their goal. If we see a child once a week for 30 minutes, that means that it will take 50 weeks to get 25 hours of practice!

- There is a bright spot in the Jackman et al (2012) study. The 25 hours consist of 15 therapy hours, plus 10 hours of home practice. (We’ll get back to this point in a second!)

-

The question naturally arises: Are these high frequencies of practice realistic in therapy alone?

The answer is obvious:

-

-

- Maybe…but it will take a long time, especially for students with disabilities

- Better yet…combine practice during therapy and outside of therapy – just like in the Jackman study mentioned above!

- Luckily…in school-based practice, we work in a real-life setting with colleagues who support the student! We have the unique advantage of being able to generate multiple opportunities for practice daily and weekly, whether we are present or not.

- So we can pile up practice, practice, and more practice to help our students surpass the thresholds of practice described above. Consequently, we can expedite their progress towards achieving their goals, such as walking, performing classroom tasks or activities of daily living (ADLs).

-

Show and Tell: Maximizing Opportunities for Practice

There are multiple ways we can provide services in the schools. Here is a small sampling:

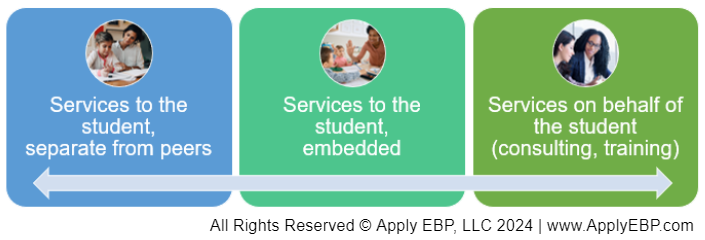

This shows a snippet of the continuum of service delivery, from the more restrictive in the left, to the less restrictive:

-

-

- “Services to the student, separate from peers” are commonly called direct pull-out services

- “Services to the student, embedded” are usually called direct push-in services (though we prefer the word embedded or integrated)

- “Services on behalf of the student” are provided via coaching, consulting or training other adults

-

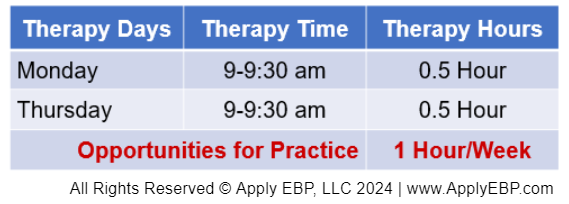

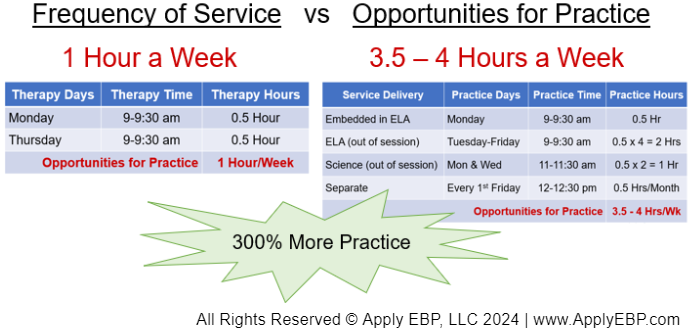

Sharing Scenario 1: Frequency of Services

Let’s say Johnny only receives “services to the student, separate from peers” twice a week for 30 minutes, and that is the only time that he practices that particular skill. Using the table below, we can explain that in this scenario of pull-out services, Johnny’s total practice time is 1 hour a week.

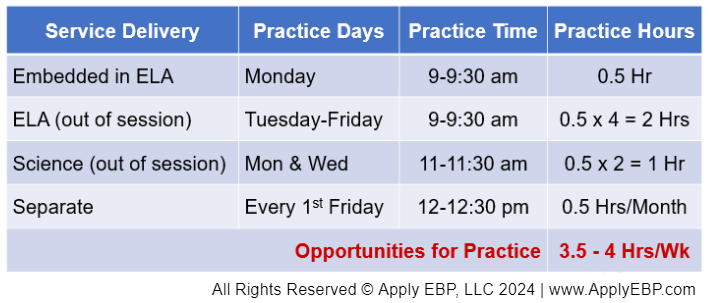

Sharing Scenario 2: Opportunities for Practice

As an alternative, we can show them the table below where we are providing services to Johnny across the continuum of service delivery.

Suppose we offer embedded services during ELA on Mondays, 9-9:30 am, granting 0.5 hour of weekly practice. Leveraging our presence in the classroom, we model and coach the staff to provide further practice opportunities during ELA on Tuesdays through Fridays, resulting in an additional 2 hours of practice weekly. Assuming the adults apply the same strategies in science class on Mondays and Wednesdays, we secure another hour of practice. Additionally, we allocate “services to the student, separate from peers” to refine their skills 30 minutes monthly during recess. This accumulates to a total of 3.5 – 4 hours of practice per week.

Sharing the Comparison between Scenarios 1 and 2

Juxtaposing these two tables allows us to illustrate the profound impact of diverse service delivery methods. We can explain that by combining weekly 30-minute sessions in class with monthly sessions in a separate location, we can generate a wealth of practice opportunities for Johnny, exceeding those provided by seeing him twice a week for 30 minutes in a separate location by up to 300%.

Another Option for Sharing:

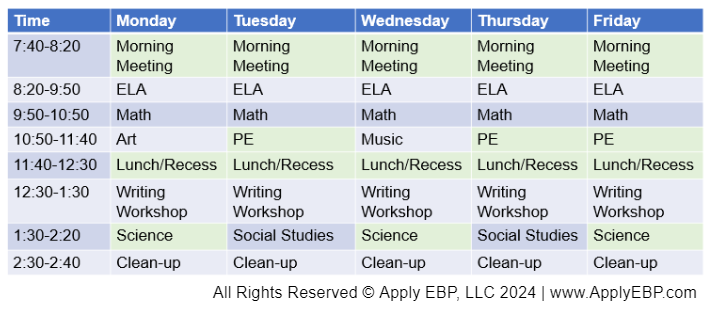

An alternative approach is to present the student’s schedule visually, highlighting opportunities for practice throughout the week. In the example below, because we embed in the class 30 minutes once a week and provide coaching to the adults during that time, we can highlight in green all the practice opportunities generated. Adding up all the green blocks showcases the cumulative practice time, indicating that our weekly 30-minute session has generated 8 hours of practice opportunities for Johnny.

Fostering Lasting Change

Introducing the concept of “opportunities for practice” may require gradual acceptance from families and educators, as it represents a shift in conversation and potentially a change in school culture. Hence, it’s essential to revisit this discussion multiple times throughout the year.

For instance, at the beginning of the school year, collaborating with teachers to identify optimal practice times can lay a foundation for understanding. Additionally, during parent-teacher conferences, presenting tables highlighting practice opportunities can reinforce the value of this approach to families. By consistently emphasizing the importance of practice opportunities, we gain support and understanding from the team when it’s time for an IEP meeting.

Conclusion: Reframing the Conversation

Here are Apply EBP’s 3 lessons for presenting amount of services:

-

-

- Switch the conversation from frequency or amount of services to the “opportunities for practice” as backed by evidence.

- Use visual aids to depict the “opportunities for practice” we can generate by combining different service delivery methods.

- Don’t wait until the IEP meeting! Cultivate understanding by regularly communicating “opportunities for practice” with families and educators throughout the school year.

-

This is not just lip service. Ultimately, what matter are results! By leveraging evidence and maximizing opportunities for practice, our ultimate show-and-tell at the IEP meeting is sharing and celebrating the goals achieved by our students!

If you are interested in more evidence-based discussions about decision-making and embedded services…

Or these webinars…

References:

Adolph, K. E., Cole, W. G., Komati, M., Garciaguirre, J. S., Badaly, D., Lingeman, J. M., … & Sotsky, R. B. (2012). How do you learn to walk? Thousands of steps and dozens of falls per day. Psychological science, 23(11), 1387-1394.

Dannemiller, L., Mueller, M., Leitner, A., Iverson, E., & Kaplan, S. L. (2020). Physical therapy management of children with developmental coordination disorder: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline from the Academy of Pediatric Physical Therapy of the American Physical Therapy Association. Pediatric physical therapy, 32(4), 278-313.

Jackman, M., Lannin, N., Galea, C., Sakzewski, L., Miller, L., & Novak, I. (2020). What is the threshold dose of upper limb training for children with cerebral palsy to improve function? A systematic review. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 67(3), 269-280.

Find More Answers to Your Questions in Our...

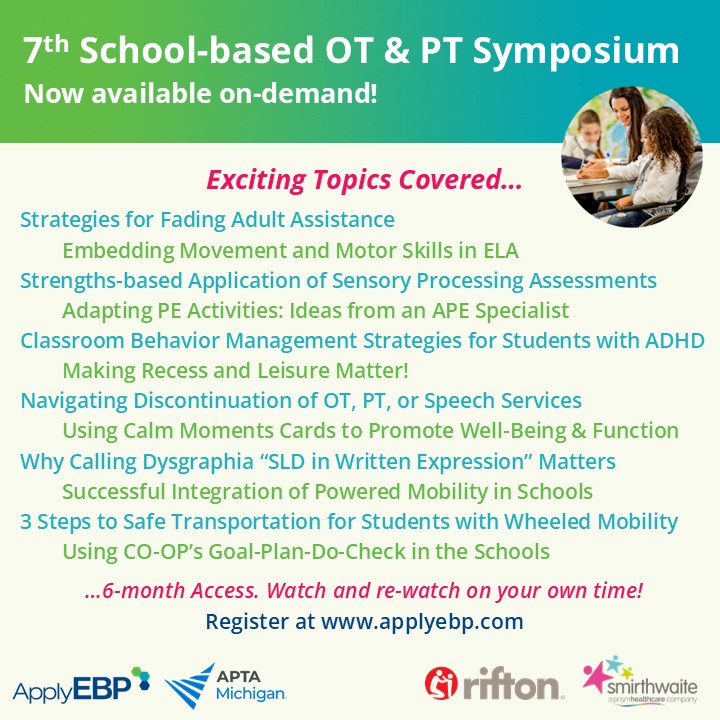

Featured School

Symposium

7th Online School-based OT and PT Symposium - On-Demand Version

- Watch and re-watch on your own time

- On-Demand Version

- OTs, OTAs, PTs and PTAs

- $399-449

Featured Live

Workshop

6th Online School-based OT and PT Symposium - On-demand Version

- Watch and re-watch on your own time

- On-Demand Version

- OTs, OTAs, PTs and PTAs

- $399-449

Featured On-Demand

Webinar

Explaining Medical-based vs School-based Services

Featured Webinar

Bundle

The IEP Process, Documentation & Conflict Resolution Bundle

Have a question?

Submit here…

*Clicking submit will send your question directly to our email inbox. Your name and email will let us know that your submission is real (not spam). We will not include these in our posts, unless you tell us to include your name. Please read our privacy policy here.

All infographics and videos on www.applyebp.com are intellectual properties of Apply EBP, LLC

You may use the infographics and videos for free for any non-commercial, educational purposes. Please cite the source as “Apply EBP, LLC” and a link to the source article. If you plan to use any infographic or video for commercial purposes (i.e., for profit), please email Carlo@applyebp.com to obtain a written permission. Permission can be granted on a case-by-case basis.